Catastrophic crack propagation is what makes a balloon pop. Could low-lying clouds similarly break up and vanish abruptly?

Could peak greenhouse gas concentrations in one spot break up droplets into water vapor, thus raising CO₂e and propagating break-up of more droplets, etc., to shatter entire clouds?

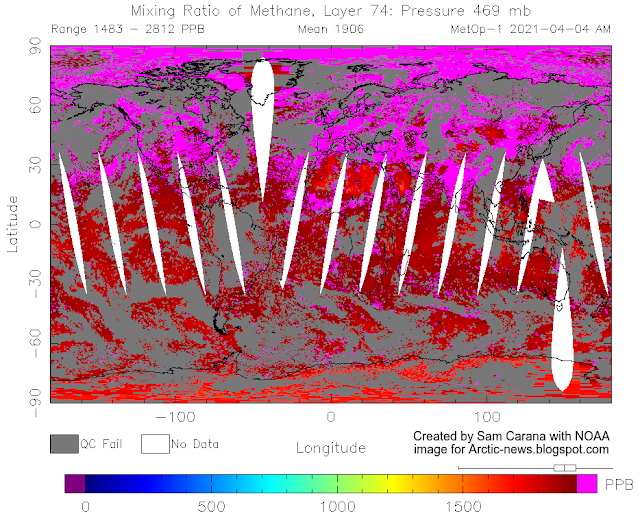

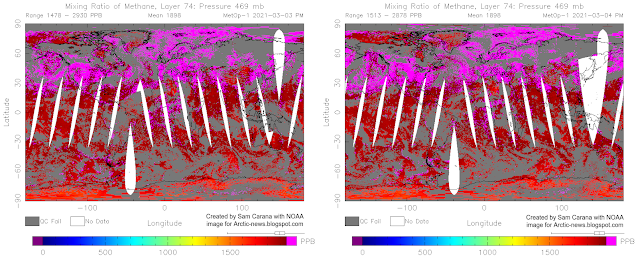

In other words, an extra burst of methane from the seafoor of the Arctic Ocean alone could suffice to trigger the clouds tipping point and abruptly push temperatures up by an additional 8°C.

Omnicide?

This brings the IPCC views and suggestions into question. As discussed above, for the average temperature to come down to below 1.5°C over the period 1997-2026, temperatures would need to fall over the next few years. What again would it take for temperatures to fall over the next few years?

Imagine that all emissions of greenhouse gases by people would end. Even if all emissions of greenhouse gases by people could magically end right now, there would still be little or no prospect for temperatures to fall over the next few years. Reasons for this are listed below, and it is not an exhaustive list since some things are hard to assess, such as whether oceans will be able to keep absorbing as much heat and carbon dioxide as they currently do.

By implication, there is

no carbon budget left. Suggesting that there was a carbon budget left, to be divided among polluters and to be consumed over the next few years, that suggestion is irresponsible. Below are some reasons why the temperature is likely to rise over the next few years, rather than fall.

How likely is a rise of more than 3°C by 2026?

• The warming impact of carbon dioxide reaches its peak

a decade after emission, while methane's impact over ten years is huge, so the warming impact of the greenhouse gases already in the atmosphere is likely to prevent temperatures from falling and could instead keep raising temperatures for some time to come.

• Temperatures are currently suppressed. We're in a La Niña period, as illustrated by the

image below.

|

| [ click on images to enlarge ] |

As

NASA describes, El Niño events occur roughly every two to seven years. As temperatures keep rising, ever

more frequent strong El Niño events are likely to occur.

NOAA anticipates La Niña to re-emerge during the fall or winter 2021/2022, so it's likely that a strong El Niño will occur between 2023 and 2025.

• Rising temperatures can cause growth in sources of greenhouse gases and a decrease in sinks. The image below shows how El Niño/La Niña events and growth in CO₂ levels line up.

• We're also at a low point in the

sunspot cycle. As the image on the right shows, the number of sunspots can be expected to rise as we head toward 2026, and temperatures can be expected to rise accordingly. According to

James Hansen et al., the variation of solar irradiance from solar minimum to solar maximum is of the order of 0.25 W/m⁻².

• Add to this the impact of a recent

Sudden Stratospheric Warming event. We are currently experiencing the combined impact of three short-term variables that are suppressing the temperature rise, i.e. a Sudden Stratospheric Warming event, a La Niña event and a low in sunspots.

Over the next few years, in the absence of large volcano eruptions and in the absence of Sudden Stratospheric Warming events, a huge amount of heat could build up at surface level. As the temperature impact of the other two short-term variables reverses, i.e. as the sunspot cycle moves toward a peak and a El Niño develops, this could push up temperatures substantially. The world could be set up for a perfect storm by 2026, since sunspots are expected to reach a peak by then and since it takes a few years to move from a La Niña low to the peak of an El Niño period.

• Furthermore, temperatures are currently also suppressed by sulfate cooling. This impact is falling away as we progress with the necessary transition away from fossil fuel and biofuel, toward the use of more wind turbines and solar panels instead. Aerosols typically fall out of the atmosphere within a few weeks, so as the transition progresses, this will cause temperatures to rise over the next few years. Most sulfates are caused by large-scale industrial activity, such as coal-fired power plants and smelters. A significant part of sulphur emissions is also caused by volcanoes. Historically, some 20 volcanoes are actively erupting on any particular day. Of the 49 volcanoes that erupted during 2021,

45 volcanoes were still active with continuing (for at least 3 months) eruptions as at March 12, 2021.

• Also holding back the temperature rise at the moment is the buffer effect of thick sea ice in the Arctic that consumes heat as it melts. As Arctic sea ice thickness declines, more heat will instead warm up the Arctic, resulting in albedo changes, changes to the Jet Stream and possibly trigger huge releases of methane from the seafloor. The rise in

ocean temperature on the Northern Hemisphere looks very threatening in this regard (see image on the right) and many of these developments are discussed at the

extinction page. There are numerous further feedbacks that look set to start kicking in with growing ferocity as temperatures keep rising, such as releases of greenhouse gases resulting from permafrost thawing and the decline of the snow and ice cover. Some 30 feedbacks affecting the Arctic are discussed at the

feedbacks page.

• The conclusion of study after study is that the situation is worse than expected and will get even worse as warming continues. Some examples: a

recent study found that the Amazon rainforest is no longer a sink, but has become a source, contributing to warming the planet instead;

another study found that soil bacteria release CO₂ that was previously thought to remain trapped by iron;

another study found that forest soil carbon does not increase with higher CO₂ levels;

another study found that forests' long-term capacity to store carbon is dropping in regions with extreme annual fires; a

recent post discussed a study finding that at higher temperatures, respiration rates continue to rise in contrast to sharply declining rates of photosynthesis, which under business-as-usual emissions would nearly halve the land sink strength by as early as 2040; the post also mentions a

study on oceans that finds that, with increased stratification, heat from climate warming less effectively penetrates into the deep ocean, which contributes to further surface warming, while it also reduces the capability of the ocean to store carbon, exacerbating global surface warming; finally,

a recent study found that kelp off the Californian coast has collapsed. So, both land and ocean sinks look set to decrease as temperatures keep rising, while a

2020 study points out that the ocean sink will also immediately slow down as future fossil fuel emission cuts drive reduced growth of atmospheric CO₂.

Where do we go from here?

The same blue trend that's in the image at the top also shows up in the image on the right, from an

earlier post, together with a purple trend and a red trend that picture even worse scenarios than the blue trend.

The purple trend is based on 15 recent years (2006-2020), so it can cover a 30-year period (2006-2035) that is centered around end December 2020. As the image shows, the purple trend points at a rise of 10°C by 2026, leaving little or no scope for the current acceleration to slow, let alone for the anomaly to return to below 2°C.

The red trend is based on a dozen recent years (2009-2020) and shows that the 2°C threshold could already have been crossed in 2020, while pointing at a rise of 18°C by 2025.

In conclusion, temperatures could rise by more than 3°C by the end of 2026, as indicated by the blue trend in the image at the top. At that point, humans will likely

go extinct, making it in many respects rather futile to speculate about what will happen beyond 2026. On the other hand, the right thing to do is to help avoid the worst things from happening, through comprehensive and effective action as described in the

Climate Plan.

Links

• Climate Plan

• NOAA Global Climate Report - February 2021 - Monthly Temperature Anomalies Versus El Niño

• NOAA Northern Hemisphere Ocean Temperature Anomaly

• NOAA Sunspots - solar cycle progression

• Smithsonian Institution - Volcanoes - current eruptions

• IPCC Special Report Global Warming of 1.5 ºC - Summary for Policy Makers

• IPCC AR5 WG1 Summary for Policymakers - Box SPM.1: Representative Concentration Pathways

• IPCC AR5, Climate Change (2013), Chapter 8