by Andrew Glikson

Precis

21–23ʳᵈ centuries’ transient ocean cooling events (stadials), triggered by ice melt flow from the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets into the adjacent oceans, herald conditions analogous in part to those of the Younger Dryas stadial (12.9–11.7 kyr) which succeeded the pre-Holocene Bölling-Allerod thermal maximum. The subsequent Younger Dryas cooling event was associated with penetration of polar air masses and ocean currents, leading to storminess, analogous to recent breaching of the weakened polar jet stream boundary, ensuing in major snow storms in North America and Europe and cooling of parts of the North Atlantic Ocean and parts of the circum-Antarctic ocean triggered by the flow of ice melt water from melting glaciers.

21–23ʳᵈ Centuries’ Stadial freeze events

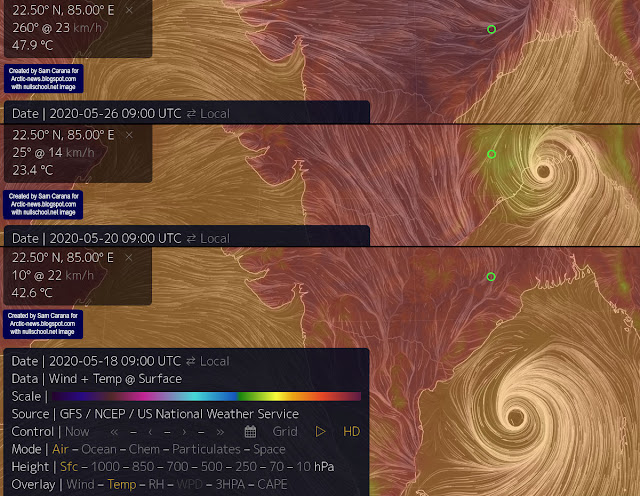

IPCC climate change projections for 2100-2300 portray linear to curved temperature progressions (SPM-5). By contrast, examination of transient cooling events (stadials) which ensued from the flow of ice melt water into the oceans during peak interglacial warming events portray abrupt temperature variations (Fig. 1). The current flow of ice melt water from Greenland and Antarctica ensuing from Anthropogenic global warming is leading to regional ocean cooling in the North Atlantic near Greenland and around Antarctica (Rahmstorf et al, 2015; Hansen et al. (2016); Bronselaer et al. 2018; Purkey et al. 2018; Vernet et al. 2019) (Fig. 2). The incipient developments of ice melt-derived cold water pools in ocean regions adjacent to the large ice sheets imply portents of future stadial events such as, inexplicably, are not indicated by the predominantly linear IPCC climate projections for the 21–23ʳᵈ centuries (IPCC AR5). By contrast, as modelled by Hansen et al. (2016) and Bronselaer et al. (2018), under high greenhouse gas and temperature rise trajectories (RCP8.5), the ice meltwater flow into the oceans from the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets would lead to cooling of large regions of the ocean, with major consequences for future climate projections. This would include the build-up of large cool ocean pools in the North Atlantic south of Greenland (Rahmstorf et al, 2015) (Fig. 2A) and around Antarctica (Fig. 2B).

Depending on different greenhouse emission scenarios (IPCC 2019; van Vuren et. al. (2011), including the CO₂ forcing-equivalents of methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O), the total CO₂–equivalent rise amounts to 496 ppm (NOAA, 2019), close to transcending the melting points of large parts of the Greenland and Antarctica ice sheets. Given the extreme rise in temperature since the mid-20th Century, where the oceans heat contents is rising, an incipient cooling of near-surface sub-Greenland and sub-Antarctic ocean regions raises the question whether incipient stadial events, perhaps analogous to the Younger Dryas stadial (Johnsen et al. 1972; Severinghaus et al. 1998), may be developing?

Interglacials, late Pleistocene and early Holocene stadial events

Stadial effects in the late Pleistocene record follow peak interglacial temperatures (Cortese et al., 2007) (Fig. 1). During the last glacial termination (LGT) stadial effects included the Oldest Dryas at ~16 kyr, the Older Dryas at ~14 kyr and the Younger Dryas at 12.9 - 11.7 kyr (Fig. 3), the latter with sharp transitions as short as 1 to 3 years (Steffensen et al., 2008), signifying a return to glacial conditions. A yet younger stadial event is represented at ~8.4 - 8.2 kyr when large-scale melting of the Laurentian ice sheet ensued in the discharge of cold water via Lake Agasiz (Matero et al. 2017; Lewis et al., 2012) into the North Atlantic Ocean. The Laurentian cooling involved temperature and CO₂ decline of ~25 ppm over ~300 years (Fig. 3B and C) and a decline of the North Atlantic Thermohaline circulation.

Greenland and Antarctica ice melt events

Oxygen isotopes (¹⁸O/¹⁹O), argon isotopes (⁴⁰Ar/³⁹Ar) and nitrogen isotopes (¹⁵N/¹⁴N) studies of Greenland ice cores (Johnsen et al. 1972; Severinghaus et al. 1998) indicate a rise in temperature to -36°C, followed by a sharp fall to -50°C (Table 1; Fig. 3A). At lower latitudes the mean temperatures drop about -2°C and 6°C (Table 1). In the southern hemisphere temperatures dropped by about -2°C in lower latitudes and about -8°C at high latitudes and (Fig. 4; Table 1) Shakun and Carlson, 2010).

Table 1.

Cooling intervals (stadial events) during late Pleistocene and early Holocene interglacial phases.

|

| Figure 4. Magnitude of late Holocene glacial-interglacial temperature changes in relation to latitude. Black squares are the Northern Hemisphere (NH), gray circles the Southern Hemisphere (SH) (Shakun and Carlson, 2010) |

Antarctic ice melt dynamics

Circum-Antarctic surface air temperatures, precipitation and sea-ice cover (Bronselaer et al. (2018), including testing the effects of ice-shelf melting, identifies penetration of relatively warm circumpolar deep water below 400 m into the grounding line underlying the ice shelf (Figs 5, 6A). The flow of ice melt water into the adjacent ocean forms an upper cold water layer away from ice shelf areas (Figure 6B). These authors indicate the flow of ice-sheet meltwater results in a decrease of global atmospheric warming, shifts rainfall northwards, and increases sea-ice area and offshore subsurface Antarctic Ocean temperatures.

In turn warmer salty water from the circum-polar deep water (CDW) from the circum-Antarctic current can penetrate below the cold off-shelf layer, as is the case in the Weddell Sea Gyre (Figures 5, 6 and 7).

|

| Figure 7. Penetration of relatively warm and salty water from the circum-Antarctic current below the cold off-shelf surface layer of the Weddell Sea Gyre. |

Global stadial cooling events

Hansen et al. (2016) suggest that, depending on ice melt rates of the polar ice sheets, transient cooling events (stadials) can be expected to develop at times dependent on the rates of ice melt (Fig. 8). The model is consistent with a slowdown of the Atlantic Meridional Ocean Circulation (AMOC) (Weaver et al. 2012) and the exceptional growth of a cold water region southeast of Greenland, (Rahmstorf et al, 2015). These authors suggest stadial cooling of about -2°C lasting for several decades (Fig. 8B), depending on ice melt rates, can affect temperatures in Europe and North America.

|

| Figure 8. A. Model surface air temperature (°C) change in 2055–2060 relative to 1880–1920 for modified forcings. B. Surface air temperature (°C) relative to 1880–1920 for several ice melt scenarios. |

According to Bronselaer et al. (2018) temporal evolution of the global-mean surface-air temperature (SAT) shows meltwater-induced cooling translates to a reduced rate of global warming (Fig. 9), with a maximum divergence between standard models and models which include the effects of meltwater induced cooling of 0.38 ± 0.02°C in 2055. The SAT response shows the effect of ice meltwater becomes weaker as the ocean becomes more stratified as a result of both moderate to deep level warming and cooling/freshening at the surface (Fig. 6B). As stated by the authors “We demonstrate that the inclusion in the model of ice-sheet meltwater reduces global atmospheric warming, shifts rainfall northwards, and increases sea-ice area”, and “Antarctic meltwater is therefore an important agent of climate change with global impact, and should be taken into account in future climate simulations and climate policy.”

Based on the paleoclimate record, global warming and rates of melting and surface cooling around parts of Antarctica and the North Atlantic (Fig. 2) would determine the future climate of large parts of Earth. Transient stadial cooling events, inherently associated with meters-scale sea level rise, would result in increased temperature polarities between subpolar and tropical latitudes, leading to storminess where polar-derived and tropical-derived air masses and ocean currents collide. Regional to global stadial cooing would, in principle, last as long as ice sheets remain. Once the large ice sheets are exhausted a transition takes place toward tropical Miocene-like and even Eocene-like conditions about 4 to 5 degrees Celsius warmer than Holocene climate conditions, which allowed agriculture and thereby civilization to emerge.

Dr Andrew Glikson

Earth and Paleo-climate scientist

ANU Climate Science Institute

ANU Planetary Science Institute

Canberra, Australia

Earth and Paleo-climate scientist

ANU Climate Science Institute

ANU Planetary Science Institute

Canberra, Australia

The Asteroid Impact Connection of Planetary Evolution

http://www.springer.com/gp/book/9789400763272

The Archaean: Geological and Geochemical Windows into the Early Earth

http://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783319079073

Climate, Fire and Human Evolution: The Deep Time Dimensions of the Anthropocene

http://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783319225111

The Plutocene: Blueprints for a Post-Anthropocene Greenhouse Earth

http://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783319572369

Evolution of the Atmosphere, Fire and the Anthropocene Climate Event Horizon

http://www.springer.com/gp/book/9789400773318

From Stars to Brains: Milestones in the Planetary Evolution of Life and Intelligence

https://www.springer.com/us/book/9783030106027

Asteroids Impacts, Crustal Evolution and Related Mineral Systems with Special Reference to Australia

http://www.springer.com/us/book/9783319745442