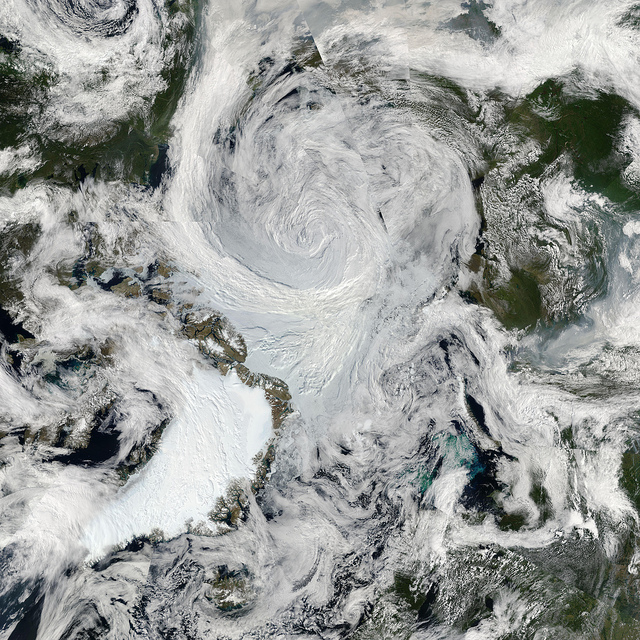

This cyclone’s central sea level pressure reached about 964 millibars on August 6, 2012—a number that puts it within the lowest 3% of all minimum daily sea level pressures recorded north of 70 degrees latitude, noted Stephen Vavrus, an atmospheric scientist based at the University of Wisconsin.

|

| Image by By NASA Goddard Photo and Video |

The combined screenshots (6 & 8 August) below from Oceanweather Inc give an idea of size of the waves churned up by the cyclone.

The storm came in from Siberia, intensified and then positioned itself over the central Arctic, engendering 20 knot winds and 50 mph wind gusts, reports Skeptical Science.

The Arctic Sea Ice Blog covered the unfolding events well, in a series of posts including:

- Cyclone warning!

- Arctic storm part 1: in progress

- Arctic storm part 2: the color purple

- Arctic storm part 3: detachment

- Further detachment

- Arctic summer storm open thread 1

Such mixing could mean that sediments that have been frozen until now get exposed to warmer water. This could destabilize methane contained in such sediments, either in the form of free gas or hydrates.

John Nissen, Chair of the Arctic Methane Emergency Group (AMEG), comments:

"There are at least three positive feedbacks working together to reinforce one another - and now a fourth on salinity:

- The albedo flip effect as sea ice is replaced by open water absorbing more sunlight, warming and melting more sea ice.

- As the sea ice gets very thin, it is liable to break up easily and get blown into open water where it will melt more easily.

- The open warmer water is allowing increased strength of storms, which break up the ice to make for more open water.

- The storms are churning up the sea to a depth of 500 metres, producing salinity at the surface that will mean slower ice formation in winter and more open water next year.

These feedbacks are dangerous for methane. AMEG has been warning that, as the sea ice retreats, storms will warm the sea bed, leading to further release of methane. In ESAS, we only need mixing to a depth of 50 metres - so a storm capable of mixing to 500 metres will really stir things up.

These feedbacks are also dangerous for food security, already damaged through climate extremes induced by Arctic warming, hence our piece in the Huffington Post.

The only way to head off catastrophe is to cool the Arctic, which must involve geoengineering as quickly as possible. We must try to remain positive and determined about this, despite the gloomy news."

These feedbacks are also dangerous for food security, already damaged through climate extremes induced by Arctic warming, hence our piece in the Huffington Post.

The only way to head off catastrophe is to cool the Arctic, which must involve geoengineering as quickly as possible. We must try to remain positive and determined about this, despite the gloomy news."

Above image shows a retreat in sea ice area to 3.15521 million km2 on the 221st day of 2012, down from 3.91533 million km2 on the 212th day of 2012, from The Cryosphere Today.

The 30-days animation below, from the Naval Research Laboratory, show the recent ice speed and drift.

The 30-days animation below, also from the Naval Research Laboratory, show recent decline of the thickness of the sea ice.