By Andrew Glikson

Abstract

As the Earth continues to heat, paleoclimate evidence suggests transient reversals will result in accentuating the temperature polarities, leading to increase in the intensity and frequency of extreme weather events.

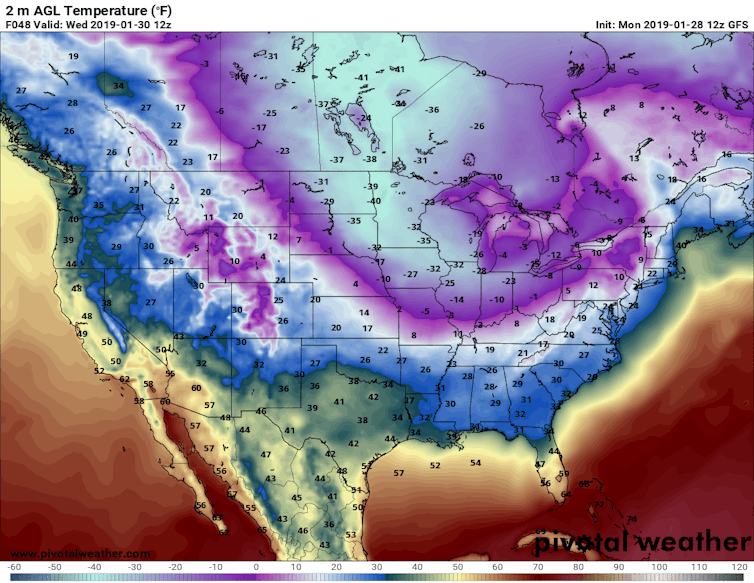

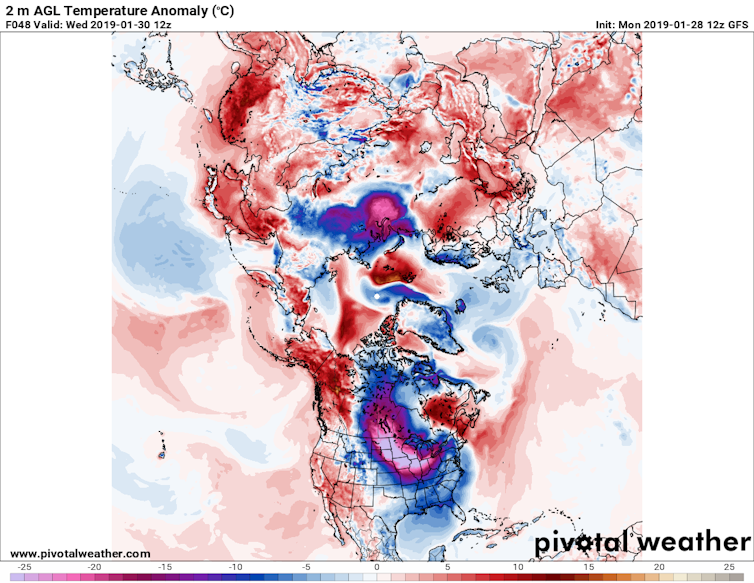

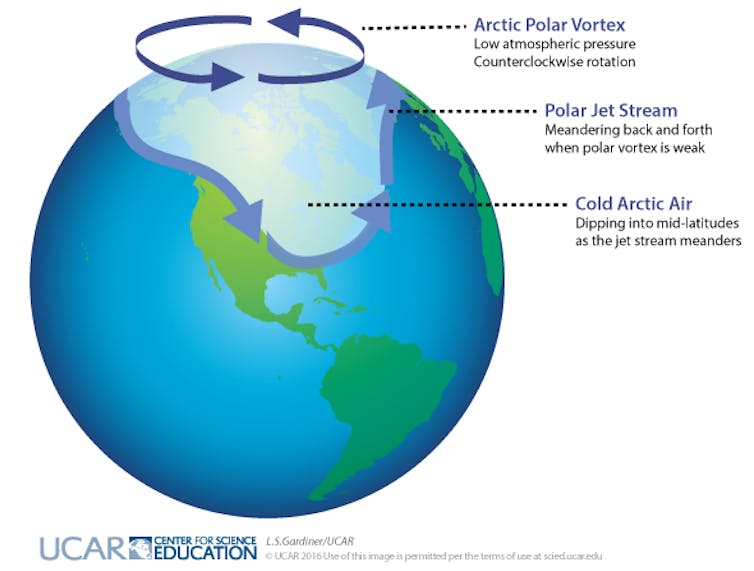

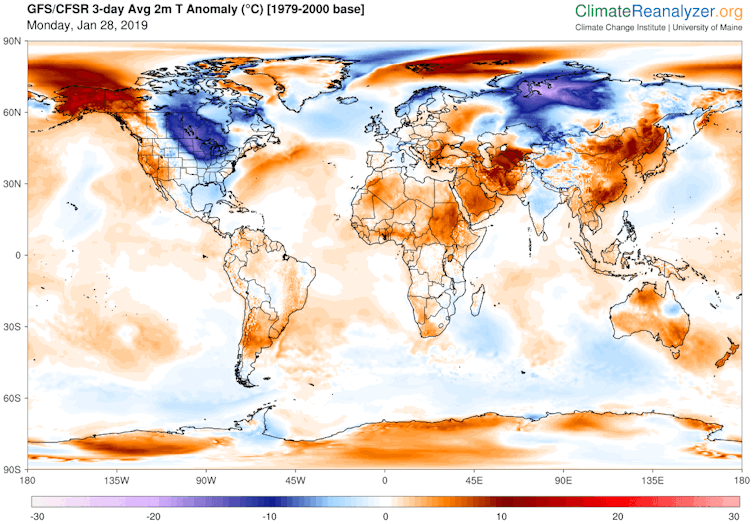

Pleistocene paleoclimate records indicate interglacial temperature peaks are consistently succeeded by transient stadial freeze events, such as the Younger Dryas and the 8.5 kyr-old Laurentide ice melt, attributed to cold ice melt water flow from the polar ice sheets into the North Atlantic Ocean. The paleoclimate evidence raises questions regarding the mostly linear to curved future climate model trajectories proposed for the 21ᵗʰ century and beyond, not marked by tipping points. However, early stages of a stadial event are manifest by a weakening of the North Atlantic overturning circulation and the build-up of a large pool of cold water south and east of Greenland and along the fringes of Western Antarctica. Comparisons with climates of the early Holocene Warm Period and the Eemian interglacial when global temperatures were about +1°C higher than late Holocene levels. The probability of a future stadial event bears major implications for modern and future climate change trends, including transient cooling of continental regions fringing the Atlantic Ocean, an increase in temperature polarities between polar and tropical zones across the globe, and thereby an increase in storminess, which need to be taken into account in planning global warming adaptation efforts.

Introduction

Reports of the International Panel of Climate Change (IPCC)⁽¹⁾, based on thousands of peer reviewed science papers and reports, offer a confident documentation of past and present processes in the atmosphere⁽²⁾, including future model projections (Figure 1). When it comes to estimates of future ice melt and sea level change rates, however, these models contain a number of significant departures from observations based on the paleoclimate evidence, from current observations and from likely future projections. This includes departures in terms of climate change feedbacks from land and water, ice melt rates, temperature trajectories, sea level rise rates, methane release rates, the role of fires, and observed onset of transient stadial (freeze) events⁽³⁾. Early stages of stadial event/s are manifest by the build-up of a large pool of cold water in the North Atlantic Ocean south of Greenland and along the fringes of the Antarctic continent (Figure 2).

|

Figure 1. IPCC AR5: Time series of global annual mean surface air temperature anomalies relative to 1986–2005

from CMIP5 (Coupled Model Inter-comparison Project) concentration-driven experiments.

Projections are shown for each RCP for the multi model mean (solid lines) and the 5–95%

range (±1.64 standard deviation) across the distribution of individual models (shading).⁽⁴⁾ |

Hansen et al. (2016) (Figure 2) used paleoclimate data and modern observations to estimate the effects of ice melt water from Greenland and Antarctica, showing cold low-density meltwater tend to cap increasingly warm subsurface ocean water, affecting an increase ice shelf melting, accelerating ice sheet mass loss (Figure 3) and slowing of deep water formation (Figure 4). Ice mass loss would raise sea level by several meters in an exponential rather than linear response, with doubling time of ice loss of 10, 20 or 40 years yielding multi-meter sea level rise in about 50, 100 or 200 years.

Linear to curved temperature trends portrayed by the IPCC to the year 2300 (Figure 1) are rare in the Pleistocene paleo-climate record, which abrupt include warming and cooling variations during both glacial (Dansgaard-Oeschger cycles; Ganopolski and Rahmstorf 2001⁽⁵⁾; Camille and Born, 2019⁽⁶⁾) and interglacial (Cortese et al. 2007⁽⁷⁾) periods. Hansen et al.’s (2016) model includes sharp drops in temperature, reflecting stadial freezing events in the Atlantic Ocean and the sub-Antarctic Ocean and their surrounds, reaching -2°C over several decades (Figure 5).

|

Figure 2. 2055-2060 surface-air temperature to +1.19°C above 1880-1920

(AIB model modified forcing, ice melt to 1 meter) From: Hansen et al. (2016)⁽⁸⁾ |

|

Figure 3. Greenland and Antarctic ice mass change. GRACE data are extension of Velicogna et al. (2014)⁽⁹⁾

gravity data. MBM (mass budget method) data are from Rignot et al. (2011)⁽¹⁰⁾. Red curves are gravity

data for Greenland and Antarctica only; small Arctic ice caps and ice shelf melt add to freshwater input.⁽¹¹⁾ |

|

Figure 4. (a) AMOC (Sverdrup⁽¹²⁾) at 28°N in simulations (i.e., including freshwater injection of 720 Gt year−1 in 2011

around Antarctica, increasing with a 10-year doubling time, and half that amount around Greenland).

(b) SST (°C) in the North Atlantic region (44–60°N, 10–50°W). |

Temperature and sea level rise relations during the Eemian interglacial⁽¹³⁾ about 115-130 kyr ago, when temperatures were about +1°C or higher than during the late stage of the Holocene, and sea levels were +6 to +9 m higher than at present, offer an analogy for present developments. During the Eemian overall cooling of the North Atlantic Ocean and parts of the West Antarctic fringe ocean due to ice melt led to increased temperature polarities and to storminess⁽¹⁴⁾, underpinning the danger of global temperature rise to +1.5°C. Accelerating ice melt and nonlinear sea level rise would reach several meters over a timescale of 50–150 years (Hansen et al. 2016)

|

Figure 5. Global surface-air temperature to the year 2300 in the North Atlantic and Southern Oceans,

including stadial freeze events as a function of Greenland and Antarctic ice melt doubling time |

Portents of collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Ocean Circulation (AMOC)

The development of large cold water pools south and east of Greenland (Rahmstorf et al. 2015⁽¹⁵⁾) and at the fringe of West Antarctica (Figures 1 and 5) signify early stages in the development of a stadial, consistent with the decline in the Atlantic Meridional Ocean Circulation (AMOC) (Figure 4). These projections differ markedly from linear model trends (Figure 1). IPCC models mainly assume long term ice melt⁽¹⁶⁾, stating “

For the 21st century, we expect that surface mass balance changes will dominate the volume response of both ice sheets (Greenland and Antarctica). A key question is whether ice-dynamical mechanisms could operate which would enhance ice discharge sufficiently to have an appreciable additional effect on sea level rise”⁽¹⁷⁾. The IPCC conclusion is difficult to reconcile with studies by Rignot et al. (2011) reporting that in 2006 the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets experienced a “

combined mass loss of 475 ± 158 Gt/yr, equivalent to 1.3 ± 0.4 mm/yr sea level rise”⁽¹⁸⁾. For the Antarctic ice sheet the IEMB team (2017) states the sheet lost 2,720 ± 1,390 billion tonnes of ice between 1992 and 2017, which corresponds to an increase in mean sea level of 7.6 ± 3.9 millimeter⁽¹⁹⁾.

A non-linear climate warming trend, including stadial freeze events, bears significant implications for planning future adaptation efforts, including preparations for transient deep freeze events in parts of Western Europe and eastern North America, for periods lasting several decades (Figure 5) and coastal defenses against enhanced storminess arising from increased temperature contrasts between the cooled regions and warm tropical latitudes.

Imminent climate risks

Climate model projections for the 21ᵗʰ to 23ʳᵈ centuries need to take paleoclimate evidence more fully into account, including the transient stadial effects of ice melt water flow into the oceans and amplifying feedbacks of global warming from land and oceans. Radiative forcing⁽²⁰], increasing with concentration of atmospheric greenhouse gases and rising by about 0.04 Watt/m²/year over the last 50 years⁽²¹⁾, totaled by more than 2 Watt/m², equivalent to ~3.0°C (~1.5°C per W/m²)⁽²²⁾. The rise of mean global temperatures to date by 0.9°C since 1880⁽²³⁾ therefore represents lag effect, pointing to potential temperature rise by approximately two degrees Celsius. A further rise in global temperatures would be enhanced by amplifying feedbacks from land and oceans, including exposure of water surfaces following sea ice melting, reduction of CO₂ concentration in water, release of methane and fires. Climate change trajectories would be highly irregular as a result of stadial events affected by flow of ice melt water into the oceans. Whereas similar temperature fluctuations and stadial events occurred during past interglacial periods (Cortese et al. 2007⁽²⁴⁾; Figure 6), when temperature fluctuations were close to ~1°C, further rises in temperature in future would enhance the intensity and frequency of extreme weather events, entering uncharted territory unlike any recorded during the Pleistocene, rendering large parts of the continents uninhabitable.

|

Figure 6. (A) Evolution of sea surface temperatures in 5 glacial-interglacial transitions recorded in ODP 1089

at the sub-Antarctic Atlantic Ocean. Lower grey lines – δ¹⁸O measured on Cibicidoides plankton;

Black lines – sea surface temperature. Marine isotope stage numbers are indicated on top of diagrams.

Note the stadial temperature drop events following interglacial peak temperatures, analogous

to the Younger Dryas preceding the onset of the Holocene (Cortese et al. 2007⁽²⁵⁾).

(B) Mean temperatures for the late Pleistocene and early Holocene. |

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above. Forward this article to your email lists.

Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

|

| Andrew Glikson |

by Andrew Glikson

Earth and Paleo-climate science, Australia National University (ANU) School of Anthropology and Archaeology,

ANU Planetary Science Institute,

ANU Climate Change Institute,

Honorary Associate Professor, Geothermal Energy Centre of Excellence, University of Queensland.

Books:

http://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783319079073

http://www.springer.com/gp/book/9789400763272

http://www.springer.com/us/book/9783319745442

http://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783319225111

http://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783319572369

http://www.springer.com/gp/book/9789400773318

Notes

(1) IPCC, Special Report, Global Warming of 1.5 ºC

https://www.ipcc.ch

https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/

(2) Climate Council, Report, The good, the bad and the ugly: limiting temperature rise to 1.5°C

https://www.climatecouncil.org.au/resources/limiting-temperature-rise/

(3) Ice melt, sea level rise and superstorms: evidence from paleoclimate data, climate modeling, and modern observations that 2 °C global warming could be dangerous, by James Hansen et al.

https://www.atmos-chem-phys.net/16/3761/2016/

(4) IPCC Climate Change 2013: Technical Summary, p.89

http://www.climatechange2013.org/images/figures/WGI_AR5_Fig12-5.jpg

http://www.climatechange2013.org/images/report/WG1AR5_TS_FINAL.pdf

(5) Rapid changes of glacial climate simulated in a coupled climate model, by Andrey Ganopolski and Stefan Rahmstorf

https://www.nature.com/articles/35051500

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11196631

(6) Coupled atmosphere-ice-ocean dynamics in Dansgaard-Oeschger events, by Camille Li and Andreas Born

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277379118305705

(7) The last five glacial‐interglacial transitions: A high‐resolution 450,000‐year record from the subantarctic Atlantic, by G. Cortese, A. Abelmann and R. Gersonde

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1029/2007PA001457

(8) Ice melt, sea level rise and superstorms: evidence from paleoclimate data, climate modeling, and modern observations that 2 °C global warming could be dangerous, by James Hansen et al. (2016)

https://www.atmos-chem-phys.net/16/3761/2016/acp-16-3761-2016-avatar-web.png

https://www.atmos-chem-phys.net/16/3761/2016/

(9) Regional acceleration in ice mass loss from Greenland and Antarctica using GRACE time‐variable gravity data, by I. Velicogna et al.

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2014GL061052

(10) Acceleration of the contribution of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets to sea level rise, by E. Rignot et al. (2011)

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2011GL046583

(11) Ice melt, sea level rise and superstorms: evidence from paleoclimate data, climate modeling, and modern observations that 2 °C global warming could be dangerous, by James Hansen et al.

https://www.atmos-chem-phys.net/16/3761/2016/acp-16-3761-2016.pdf

(12) Sverdrup: Unit of flow – 1 Sv is equal to 1,000,000 m³ per second

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sverdrup

(13) Eemian Interglacial Stage

https://www.britannica.com/science/Eemian-Interglacial-Stage

(14) Giant boulders and Last Interglacial storm intensity in the North Atlantic, by Alessio Rovere et al. (2017)

http://moraymo.us/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Rovereetal_PNAS_2017.pdf

Northern hemisphere winter storm tracks of the Eemian interglacial and the last glacial inception, by F. Kaspar (2006)

https://www.clim-past.net/3/181/2007/cp-3-181-2007.pdf

(15) Exceptional twentieth-century slowdown in Atlantic Ocean overturning circulation, by Stefan Rahmstorf et al. (2015)

https://www.nature.com/articles/nclimate2554

(16) The UN's Devastating Climate Change Report Was Too Optimistic, by Nafeez Ahmed (Oct 16, 2018)

https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/43e8yp/the-uns-devastating-climate-change-report-was-too-optimistic

(17) IPCC Third Assessment Report, Working Group I: The Scientific Basis

https://archive.ipcc.ch/ipccreports/tar/wg1/416.htm

(18) Acceleration of the contribution of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets to sea level rise, by E. Rignot et al. (2011)

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1029/2011GL046583

(19) Mass balance of the Antarctic Ice Sheet from 1992 to 2017

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-018-0179-y.epdf

(20) Radiative forcing – the difference between incoming radiation and radiation reflected back to space

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Radiative_forcing

(21) Climate Change in a Nutshell: The Gathering Storm, by James Hansen (18 December 2018)

http://www.columbia.edu/~jeh1/mailings/2018/20181206_Nutshell.pdf

(22) Target atmospheric CO2: Where should humanity aim?, by James Hansen (2008)

https://arxiv.org/abs/0804.1126

(23) NASA: Global temperature

https://climate.nasa.gov/vital-signs/global-temperature/

(24) The last five glacial‐interglacial transitions: A high‐resolution 450,000‐year record from the subantarctic Atlantic, by G. Cortese, A. Abelmann and R. Gersonde

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1029/2007PA001457

(25) The last five glacial‐interglacial transitions: A high‐resolution 450,000‐year record from the subantarctic Atlantic, by G. Cortese, A. Abelmann and R. Gersonde

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1029/2007PA001457

This is an edited version of an article at

Global Research

Copyright ©

Dr. Andrew Glikson, 2019

Surface air temperatures near Svalbard were as high as 5.2°C or 41.4°F near Svalbard on February 3, 2019. At the same time, it was as cold as -3.5°C or 25.6°F in Africa.

Surface air temperatures near Svalbard were as high as 5.2°C or 41.4°F near Svalbard on February 3, 2019. At the same time, it was as cold as -3.5°C or 25.6°F in Africa.

On December 8, 2018, the sea surface temperature near Svalbard was 18.2°C or 32.7°F warmer than 1981-2011. On January 23, 2019, sea surface temperatures at that spot were as high as 18.3°C or 64.9°F, as illustrated by the image on the right, from an earlier post.

On December 8, 2018, the sea surface temperature near Svalbard was 18.2°C or 32.7°F warmer than 1981-2011. On January 23, 2019, sea surface temperatures at that spot were as high as 18.3°C or 64.9°F, as illustrated by the image on the right, from an earlier post.