|

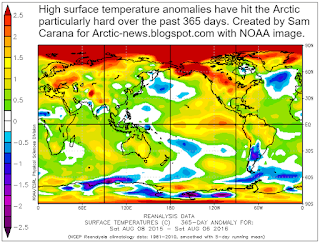

| Professor Schuiling in front of a huge and very impressive olivine massif in Oman |

Olivine weathering to capture CO₂ and counter climate change - by R.D. Schuiling

Abstract

CO₂ is emitted in large quantities as a consequence of our burning of fossil fuels. It has several unpleasant consequences, because it will probably cause climate change, and there are several reports that high levels of CO₂ in offices and schools may impair the quality of thinking of the people that work there. Although higher levels of it in the atmosphere may also have some beneficial effects on vegetation, it should be considered as a possibly dangerous pollutant.

Introduction

Many new technologies are proposed to remove CO

₂ from the atmosphere, but strangely enough the only process that has always removed the excess of CO

₂ emitted by volcanoes since the origin of the Earth is barely considered. It is the weathering of minerals by which almost all the CO

₂ that was emitted during the past by volcanoes was transported as bicarbonate solutions to the oceans where it was sustainably stored as carbonate rocks (limestones and dolomites).

Mg₂(SiO₄) + 4 CO₂ + 4 H₂O → 2 Mg²⁺ + 4 HCO3- + H₄(SiO₄)

These rocks contain about 1 million times more CO

₂ than the oceans, the atmosphere and the biosphere combined. It has provided a livable atmosphere, in contrast with Venus, where weathering was impossible due to the lack of liquid water. At present the CO

₂ levels in the atmosphere are rising, because the anthropogenic emission of CO

₂ is so large that this weathering process cannot keep pace with it. I propose to use a process of enhanced weathering to regain a new balance between input and output. In order to make this cost-effective, my examples will all represent a combination of CO

₂ capture with another beneficial effect, by which the total effect is cheaper, and may occasionally even lead to a positive financial result.

Ten cost-effective applications of olivine weathering:

- Increasing rice production by spreading olivine grains in paddies

- Olivine spreading on acid soils instead of liming

- Biogas production with additional methane production

- Solution of the sick-building syndrome of schools and offices

- The use of the surf as a huge ball-mill

- Diatom cultivation for the production of biodiesel

- Phytomining of nickel from olivine-rich soils

- Olivine hills to produce healthy mineral water

- Quenching forest fires with a serpentine slurry

- Tackling natural emissions in Milos, Greece

1. Increasing rice production by spreading olivine grains in paddies

Rice, like the other “wet grasses” like bamboo and reed needs silica. This is made available by spreading olivine grains over the paddies. It is very easy to measure the effects, by sampling the irrigation water where it enters the paddy, and sample it again where the water leaves the paddy containing olivine. The difference between the two analyses represents the effect of the weathering of the olivine. Rice production is negatively affected by acid conditions (1), and the weathering of olivine makes conditions more alkaline. As rice cultivation occupies 146 million hectares, spreading these annually with 4 ton of olivine per hectare also represents a sizable capture of CO

₂. The increase of rice production can be measured by spreading for example 1, 3 and 10 ton of olivine over 3 paddies, and compare rice production with the production of a similar paddy without olivine spreading.

2. Olivine spreading on acid soils instead of liming

The approach as sketched above for rice can be extended to other acid agricultural soils as well. Normally acid soils are remediated by liming, but olivine spreading can do the same, and captures CO

₂ at the same time, whereas liming has a penalty for its CO

₂ emissions on account of the mining, milling and transporting of lime. Tests at the Agricultural University of Wageningen (2) have shown that olivine application increases productivity. The costs of adding lime or olivine will be rather similar, and soil scientists should decide whether a mixture of the two produces a better soil than using only one of the two.

3. Biogas production with additional methane production

Increasing methane production in biogas installations. In the normal operation of biodigesters, the produced gas contains roughly 2/3 methane, 1/3 CO

₂ and traces of H

₂S. Before this gas can be added to the national gas lines, the CO

₂ content must be drastically reduced by rather expensive operations, and the H

₂S must be removed. Tests with digesters have shown that the addition of fine-grained olivine has 3 important effects. It creates more alkaline conditions, which make that a larger part of the CO

₂ is already taken up as bicarbonate in the digestate, and does not have to be removed by expensive technologies. The second effect is that the traces of H

₂S react with the iron content of the olivine and forms solid iron sulfide particles (olivine is a mixed crystal of

Mg₂(SiO₄) and

Fe₂(SiO₄). The third effect was somewhat unexpected. The methane production increases by the following reaction:

6 Fe₂(SiO₄) + CO₂ + 14 H₂O → Fe₃O₄ + CH₄ + 6 H₄(SiO₄)

The methane reaction is catalyzed by the tiny magnetite crystals that form in this reaction. In view of the important role of iron in the olivine, it may be worthwhile to look for olivine deposits with a higher Fe-content than the usual olivine. This application will reduce the costs of the digestion, and increase its production.

4. Solution of the sick-building syndrome of schools and offices

It was recently found by research groups in Berkeley and Harvard (3,4) that the high CO

₂ content of the internal atmosphere of these buildings (rising to 1500 to 1600 ppm in the afternoon compared to 400 ppm in the atmosphere outside) impaired the quality of thinking of the inmates. To avoid this, one can open doors and windows, but in temperate climates this causes serious increases in energy costs, and will often cause dust and noise problems. One can prevent this by installing a so-called CATO-reactor (Clean Air Through Olivine). This is a trough-like basin filled with an emulsion of fine olivine grains. Along the bottom a perforated pipe is installed, through which the internal atmosphere of the building is transported under a slight overpressure. The air bubbles pass through the olivine emulsion, and the CO

₂ is converted to bicarbonate in solution. This set-up has the additional advantage that it will also trap allergenic particles or pollen, which will make life easier for people who suffer from asthma or hay fever.

5. The use of the surf as a huge ball-mill

The surf as the largest ball-mill on Earth. Milling of olivine (around 2 US$/ton for milling olivine to 100 micron) is a cost that can be avoided if nature provides a zero cost alternative. We have carried out experiments with angular coarse olivine grit in a simulated very modest surf (5). After a few days the grains were rounded and polished grains (Fig. 1). Tiny micron-sized slivers were knocked off by collisions and abrasion. These slivers weathered in a few days.

|

| Fig 1: The surf turns angular coarse olivine grit into rounded and polished grains in a few days |

Depositing coarse olivine grit directly on beaches in the surf may well become the cheapest large-scale way to capture CO

₂ and restore the pH of the oceans.

6. Diatom cultivation for the production of biodiesel

Diatom cultivation for biodiesel production. Biofuels are produced at fairly large scale from oil palms, sorghum, maize and the like. This production occupies large tracts of land, which are withdrawn from the world food production. They consume large volumes of irrigation water, and use expensive fertilizer. Moreover not seldomly reservations for threatened animals, like the orang outan are used for these plantations. Enough reasons to look for different solutions. Diatoms (silica algae) are rich in organic material from which biodiesel can be produced. They are called silica algae, because their exoskeleton is made of silica. They can multiply fast, provided that they have enough silica. This can be provided by the weathering of olivine. One can think of the following solution for diatom cultivation. Create a lagoon along the beach, by surrounding a piece of the sea in front of this beach by a dam. Construct a connection through this dam, through which water can flow into the lagoon at high tide, and flow out of the lagoon at ebb tide. Cover the beach with half a meter thick layer of olivine grains between the high tide line and the low tide line. This beach will alternatively be wetted and drained, by which the silica-rich water will flow into the lagoon, and feed the diatoms. The dead diatoms must be harvested, dried and transported to the biodiesel plant . The diatom production in the lagoon can be boosted by installing an underwater led lighting, which makes that the photosynthesis of the diatoms can continue through the night.

7. Phytomining of nickel from olivine-rich soils

Phytomining of nickel. Olivine contains more nickel than most rocks, but still much lower than nickel ores. There are a number of plant species that have the strange habit that they can extract nickel very well from the soils on olivine rock and store it in their tissues . When you harvest these plants at the end of the growing season, dry them and burn them, the plant ash often contains around 10% of nickel, more than the richest nickel ore. Mining is an energy-intensive affair and has a high CO

₂ emission. Moreover the mining and the metal extraction from the ore cause a lot of pollution. This makes it tempting to see if you can use these nickel hyperaccumulator plants to do the job of mining without large CO

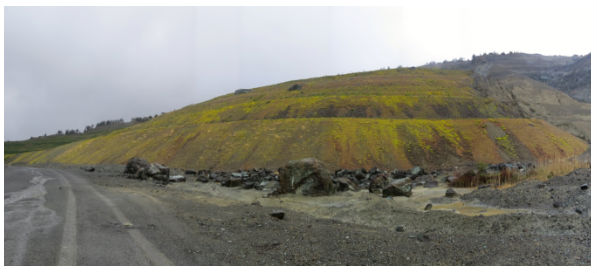

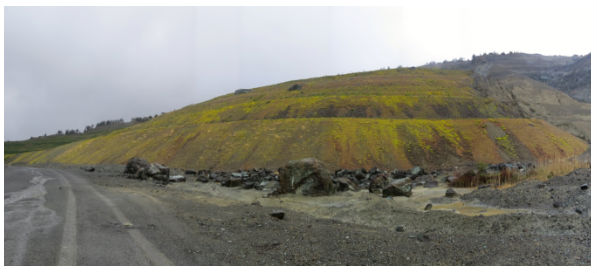

₂ emissions (6). Figure 2 shows the flowering Alyssum plants (a well-known nickel hyperaccumulator plant) on the tailings of an asbestos mine in Cyprus.

|

| Fig 2: Yellow blossomed Alyssum nickel hyperaccumulator plants grow on tailings of former asbestos mine on Cyprus |

8. Olivine hills to produce healthy mineral water

Olivine hills to produce healthy mineral water. When olivine weathers, it turns the water into a healthy magnesium bicarbonate water. According to the FAO such waters are active against cardiovascular diseases. This makes it interesting to see if we can produce similar mineral waters in places where there is no olivine in the subsoil. This is possible by the use of olivine hills (7). These can be constructed as follows. First make an impermeable layer on the soil in the form of a very flat slightly inclined gutter. Cover this with a hill of olivine grains of several meter thickness. Add soil over this hill, and plant it with shrubs and grasses. Soils are much richer in CO

₂ than the atmosphere. This is caused by the decay of dead plant material which produces CO

₂ in the soil, as well as the breathing of animals living in this soil. When it rains, the water will first encounter this CO

₂-rich soil atmosphere, equilibrate with it and become aggressive. This CO

₂-rich water will then move into the olivine layer, and react with it, producing a healthy magnesium bicarbonate water. This will trickle through the olivine layer until it meets the impermeable base, where it will slowly trickle to the lowest point of the gutter, where it will be released through a tap, where visitors can collect some of this water and drink it.

9. Quenching forest fires with a serpentine slurry

Quenching forest fires with a serpentine slurry. Forest fires cause the largest emission of CO

₂ after the emission by burning fossil fuels (8). Large forest fires lead to a number of deaths. Both from the public health side as from the CO

₂ emission side it would be helpful if we found a better way to quench forest fires rapidly. The following seems to be a promising way to achieve this. Serpentine is the hydrated form of olivine, it is similar to clay minerals. It is well-known that baking clays to make bricks consume a lot of energy. This is an unpleasant property, except where it is important to remove as much heat as possible, like in forest fires. We carried out a number of tests to see whether spreading serpentine slurries over fires would be a more effective way to quench fires than just water. This turned out to be very clearly the case, but not for the reason we thought. Test fires were extinguished in a few seconds when serpentine slurries were sprinkled over them, but the removal of excess heat was only a minor factor in the success. When serpentine slurries are spread over burning wood, the serpentine immediately dissociates, and forms a thin amorphous layer on the burning material. Oxygen can no longer come in contact with the burning wood, and inflammable gases from the burning wood can no longer escape. Test fires were quenched in a few seconds. As serpentinites are very common rocks, it should be easy to introduce this way of quenching to combat forest fires. It is hoped that this will be introduced by the fire brigades in many countries that suffer from forest fires, and thus save unnecessary deaths and destruction of properties. The amorphous product of the serpentine after it has reacted in the fire reacts quite fast with the first rains, faster than olivine, and thus compensates part of the CO₂ that was emitted by the fire.

10. Tackling natural emissions in Milos, Greece

CO₂ levels in the atmosphere are rising, because we are burning in a few hundred years the fossil fuels (coal, oil, gas) that have taken hundreds of millions of years to form. This will probably cause a climate change, with disastrous world problems, because the ice in Greenland and Antarctica will melt and cause a serious sealevel rise. It is important, therefore, to capture as much CO₂ as possible and store it in a safe and sustainable manner.

It makes no difference for the climate if we capture anthropogenic CO₂ or natural CO₂ emissions, because all CO₂ molecules are identical. The anthropogenic emissions are much more voluminous, but natural emissions are easier to capture. An excellent example is found on and around the island of Milos, where annually 2.2 million tons of hot CO₂ are emitted from a surface area of about 35 km². The village of Paleochori is the center of this CO₂ emission. Most of the CO₂ emission is by bubbles rising out of the shallow seafloor, but CO₂ is also emitted on land. When you try to dig a hole in the beach with your hands, you have to stop when the hole is elbow-deep, otherwise you burn your hands. The bubbles are so hot, that a local restaurant in Paleochori is even using it for its “volcanic cooking”. They have buried a box in the beach sand, in which they cook a lamb every morning. Delicious to have a juicy lamb for lunch on the terrace of that restaurant, while you look out over the blue Aegean.

It becomes important for the world to capture as much CO₂ as possible. When you apply this to the CO₂ emissions at Milos, one could do the following. First find a place where the most CO₂ bubbles rise from the shallow sea floor. Then make a small artificial island by covering this point with a hill of olivine sand as well as larger olivine pieces. Of course, when bubbles of CO₂ rise in the sea, they will assume the same temperature as the sea water, but if they rise in an olivine hill they will cause the temperature inside that olivine hill to rise, because now the hot bubbles release their heat to the surrounding olivine grains. This situation will lead to a small convection system. The warm water inside the hill will start to rise, and cold seawater will be sucked in the hill from the sides. If one constructs a shallow pit on top of the island, it will fill with warm water.

Would it not be an exotic temptation for tourists, to lie even in winter in a warm bath on top of a small island, and look out over a cool blue sea? They will feel even better if they know that these delicious sensations are a small part of our efforts to save the world from climate change, and the seas from acidification. The reaction of the olivine with water + CO₂ is exothermic, so that provides some additional heat for the water in the bath.

Additional information:

As said, the weathering reaction of olivine with water and CO2 is as follows:

Mg₂(SiO₄) + 4 CO₂ + 4 H₂O → 2 Mg²⁺ + 4 HCO3- + H₄(SiO₄)

This means that the greenhouse gas CO₂ is converted to a bicarbonate solution, so it is no longer affecting the climate.

Some possible sources of olivine in Greece

Olivine is a very common mineral. The tailings of a magnesite company in northern Greece contain close to ten million tons of crushed olivine. A port is not too far from the location of that magnesite mine. Nearer by, on the island of Naxos, there are quite a few places with olivine rocks at the surface, where the material could be obtained by a small open pit digging operation. Apart from the proposal as a touristic attraction, Greece can present it as one of their attempts to sustainably capture the greenhouse gas CO₂.

Conclusion

Removal of CO₂ from the atmosphere can be combined in a number of ways with other positive effects, which makes such operations considerably more cost-effective.

References

- Breemen, N. van (1976) Genesis and solution chemistry of acid sulfate soils in Thailand. PhD thesis. Agricultural University of Wageningen, 263 pp.

http://library.wur.nl/WebQuery/wurpubs/70246

- Ten Berge, H.F.M., van der Meer, H.G., Steenhuizen, J.W., Goedhart, P.W., Knops, P. Verhagen, J. (2012) Olivine weathering in Soil, and its Effects on Growth and Nutrient Uptake in Ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). A Pot Experiment. PLOS\one, 7(8): e42098.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0042098

- Savchuk, K. (2016) Your brain on Carbon dioxide: Research finds low levels of indoor CO₂ impair thinking. California Magazine/summer 2016.

https://alumni.berkeley.edu/california-magazine/summer-2016-welcome-there/your-brain-carbon-dioxide-research-finds-even-low

- Allen, J.G., Macnaughton, P., Satish, U., Spengler, J.D. (2015) Association of cognitive function scores with carbon dioxide, ventilation, and volatile organic compound exposure in office workers: a controlled exposure study of green and conventional office environments. Env. Health Perspectives, October 2015.

https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/doi/10.1289/ehp.1510037

- Schuiling, R.D. and de Boer, P.L. (2011) Rolling stones, fast weathering of olivine in shallow seas for cost-effective CO₂ capture and mitigation of global warming and ocean acidification. Earth Syst. Dynam. Discuss., 2, 551-568. doi:10.5194/esdd-2-551.

https://www.earth-syst-dynam-discuss.net/esd-2011-20/

- Schuiling, R.D. (2013) Farming nickel from non-ore deposits, combined with CO₂ sequestration. Natural Science 5, no 4, 445-448.

https://www.scirp.org/journal/PaperInformation.aspx?paperID=29842

- Schuiling, R.D. and Praagman, E. (2011) Olivine Hills, mineral water against climate change. Chapter 122 in Engineering Earth: the impact of megaengineering projects. Pp 2201-2206. Ed.Stanley Brunn, Springer.

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007%2F978-90-481-9920-4_122

- Schuiling, R.D. (2015) Serpentinite slurries against Forest Fires. Open J. Forestry, 5, 255-259.

https://www.scirp.org/journal/PaperInformation.aspx?PaperID=54576

Further publications

• Olivine against climate change and ocean acidification, by R. D. Schuiling and Oliver Tickell (2011)