As illustrated by the above image, adapted from a NOAA forecast, a massive winter storm is forecast to hit much of the U.S. (forecast valid through January 26, 2026).

The above image, adapted from ClimateReanalyzer, shows that temperatures as low as 9°F (-12.78°C) are forecast to hit Texas on January 24, 2026.

The above image, adapted from nullschool.net, shows temperatures as low as -0.8°F (-18.12°C) forecast to hit Kansas on January 24, 20026 (at the green circle).

Temperatures in Russia

The image below shows that, on January 26, 2026, temperatures in Russia were as low as -52°F (-46.6°C) at a location in Russia at 63.5°N (green circle). This is well outside of the Arctic Circle, which is at 66°3'N. Within the Arctic Circle, sunlight is absent on the winter solstice.

Temperatures in Russia

The image below shows that, on January 26, 2026, temperatures in Russia were as low as -52°F (-46.6°C) at a location in Russia at 63.5°N (green circle). This is well outside of the Arctic Circle, which is at 66°3'N. Within the Arctic Circle, sunlight is absent on the winter solstice.

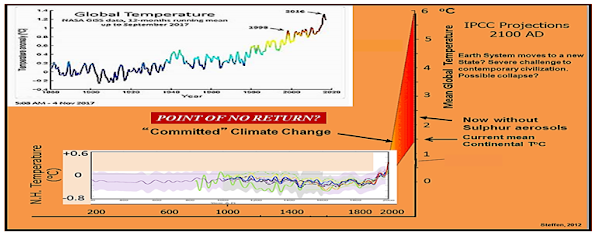

As temperatures keep rising, many feedbacks are striking with increasing vigor, resulting in higher temperature anomalies at the Arctic (polar amplification), resulting in more cold air descending deeper outside of the Arctic Circle (Jet Stream distortion), and resulting in more massive snowfall (7% more water in the air for each 1°C rise in temperature).

Jet Stream distortion and further feedbacks

For some, the cold weather forecasts may raise questions as to how this can happen, given the overwhelming scientific evidence that global temperatures are rising as a result of activities by people.

The image below may be helpful when responding to such questions. The image shows Wind + Instantaneous Wind Power Density at 250 hPa, at an altitude where the Jet Stream is strong. The image illustrates that, because temperatures over continents are low in the Northern Hemisphere at this time of year while sea surface temperature are high due to global warming, there is a strong difference between temperatures over land and temperatures over the ocean. This strong temperature difference strengthens the speed of latitudinal winds, i.e. the prevailing wind patterns that are moving east-west across Earth, driven by solar heating differences and the Coriolis effect.

|

| [ click on images to enlarge ] |

The above image shows a wind speed of 377 km/h and a Wind Power Density of 206.8 kW/m² at 250 hPa at the green circle off the coast of Japan. Furthermore, polar amplification narrows the temperature difference between the Equator and the poles, which distorts the path of the Jet Stream, resulting in circular wind patterns at higher altitudes North.

The Jet Stream used to keep cold air in the Arctic, separated from warmer air at lower latitudes. A distorted Jet Stream causes the Arctic to heat up strongly, while lower latitudes get colder, as illustrated by the image below, showing the temperature anomaly on January 24, 2026, 18z. This has been coined the 'open doors' feedback, it's like the door of the freezer is left open.

The image below shows the temperature anomaly (left) and the minimum temperature (right) on January 25, 2026, with images adapted from ClimateReanalyzer.

The combination image below further illustrates the situation on January 26, 2026. Jet Stream distortion occurs due to a narrowing of the temperature difference between the Equator and the poles, and due to a stronger temperature difference between oceans and continents. This can cause the Jet Stream to form Omega patterns and even go circular. Further feedbacks that can amplify the situation include more water vapor in the air, which can come with strong precipitation.

|

| [ click on images to enlarge ] |

The image on the left shows wind and surface temperatures; very low temperatures show up over land (Russia, Canada, Greenland), much lower than temperatures over the Arctic Ocean. The image at the center shows wind and sea surface temperature anomalies (SSTA). High SSTA show up off the east coast of Asia and off the east coast of North America. The image on the right shows wind patterns at 250 hPa, which corresponds with a Jet Stream altitude of approximately 10,500 m. A location (48°N,57°W) is highlighted by the green circle on each of the images, on at the image on the right the wind there reaches a speed of 399 km/h (or 248 mph).

The image below shows the 2025 temperature anomaly versus 1951-1980 (NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis v1). The highest anomalies show up at the poles, reflecting polar amplification of the temperature rise, caused by decline of the snow and ice cover and by further feedbacks.

|

| [ from earlier post ] |

The global temperature rise comes with many feedbacks, including more water vapor in the atmosphere, polar amplification of the temperature rise and distortion of the Jet Stream, which can at times result in unusually low temperatures over continents in the Northern Hemisphere.

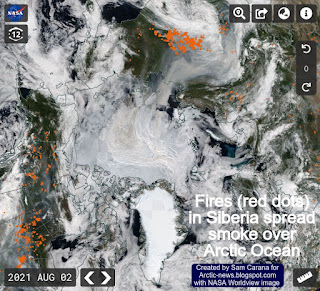

Importantly, distortion of the Jet Stream can at times also result in large amounts of ocean heat getting carried into the Arctic Ocean, abruptly heating up the water of the Arctic Ocean and threatening to destabilize methane hydrates contained in sediments at the seafloor, resulting in huge methane eruptions.

The situation is dire and unacceptably dangerous, and the precautionary principle necessitates rapid, comprehensive and effective action to reduce the damage and to improve the outlook, where needed in combination with a Climate Emergency Declaration, as described in posts such as in this 2022 post and this 2025 post, and as discussed in the Climate Plan group.

Links

• The threat of seafloor methane eruptions

https://arctic-news.blogspot.com/2025/11/the-threat-of-seafloor-methane-eruptions.html

• Feedbacks in the Arctic

https://arctic-news.blogspot.com/p/feedbacks.html

• Water Vapor Feedback

https://arctic-news.blogspot.com/2024/09/water-vapor-feedback.html

• Jet Stream

https://arctic-news.blogspot.com/p/jet-stream.html

• Opening further Doorways to Doom

https://arctic-news.blogspot.com/2012/08/opening-further-doorways-to-doom.html

• NOAA - weather forecasts

https://graphical.weather.gov

• Trump Mocks Climate Change Concerns Ahead of Historic Winter Storm. Here’s Why That’s Wrong

https://time.com/7357480/trump-winter-storm-fern-climate-change

• Wild Weather Swings

https://arctic-news.blogspot.com/2025/12/wild-weather-swings.html

• Extreme weather gets more extreme

https://arctic-news.blogspot.com/2025/08/extreme-weather-gets-more-extreme.html

• Copernicus

https://pulse.climate.copernicus.eu

• Climate Reanalyzer

https://climatereanalyzer.org

• nullschool.net

• Transforming Society

https://arctic-news.blogspot.com/2022/10/transforming-society.html

• Climate Plan

https://arctic-news.blogspot.com/p/climateplan.html

• Climate Emergency Declaration

https://arctic-news.blogspot.com/p/climate-emergency-declaration.html