In the 12 months up to July 14, 2016, 48 earthquakes with a magnitude of 4 or higher on the Richter scale hit the map area of the image below, mostly at a depth of 10 km (6.214 miles).

As temperatures keep rising and as melting of glaciers keeps taking away weight from the surface of Greenland, isostatic rebound can increasingly trigger earthquakes around Greenland, and in particular on the faultline that crosses the Arctic Ocean.

Two earthquakes recently hit the Arctic Ocean. One earthquake hit with a magnitude of 4.5 on the Richter scale on July 9, 2016. The other earthquake hit with a magnitude of 4.7 on the Richter scale on July 12, 2016, at 00:15:24 UTC, with the epicenter at 81.626°N 2.315°W and at a depth of 10.0 km (6.214 miles), as illustrated by the image below.

Following that most recent earthquake, high levels of methane showed up in the atmosphere on July 15, 2016, over that very area where the earthquake hit, as illustrated by the image below.

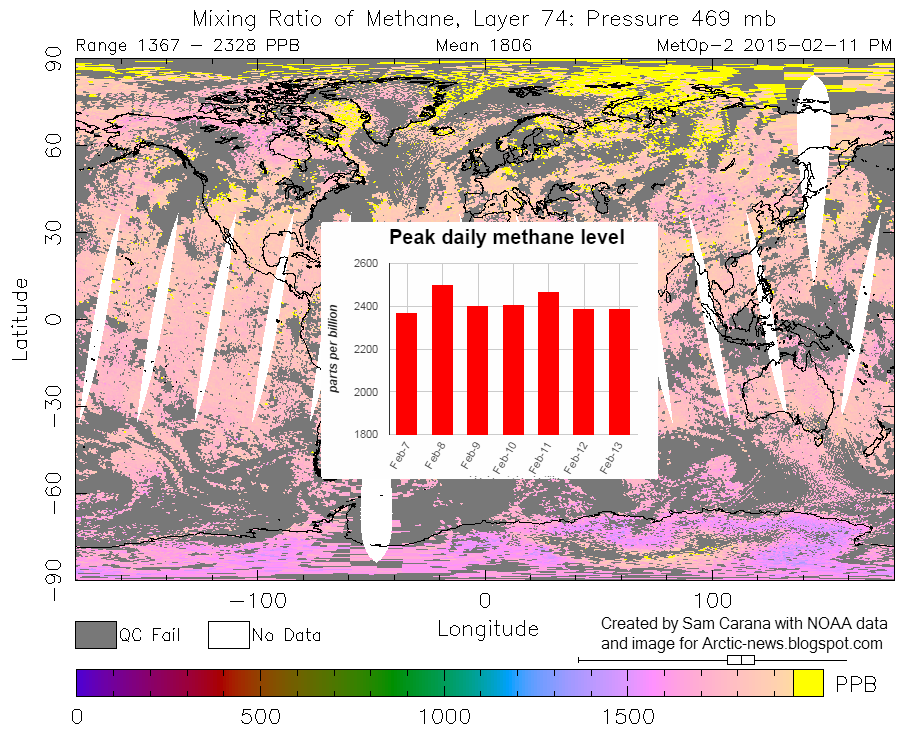

Above image shows that methane levels were as high as 2505 ppb at an altitude of 4,116 m or 13,504 ft on the morning of July 15, 2016. At a higher altitude (of 6,041 m or 19,820 ft), methane levels as high as 2598 ppb were recorded that morning and the magenta-colored area east of the north-east point of Greenland (inset) looks much the same on the images in between those altitudes. All this indicates that the earthquake did cause destabilization of methane hydrates contained in sediments in that area.

Above image, from another satellite, confirms strong methane releases east of Greenland on the afternoon of July 14, 2016, while the image below shows high methane levels on July 16, 2016, along the faultline that crosses the Arctic Ocean.

The image on the right shows glaciers on Greenland and sea ice near Greenland and Svalbard on July 15, 2016. Note that clouds partly obscure the extent of the sea ice decline.

Above image shows the sea ice on July 12, 2016. There is a large area with very little sea ice close to the North Pole (left) and there is little or no sea ice around Franz Josef Land (right). Overall, sea ice looks slushy and fractured into tiny thin pieces. All this is an indication how warm the water is underneath the sea ice.

|

| [ click on image to enlarge ] |

In addition to the shocks and pressure changes caused by earthquakes, methane hydrate destabilization can be triggered by ocean heat reaching the seafloor of the Arctic Ocean. Once methane reaches the atmosphere, it can very rapidly raise local temperatures, further aggravating the situation.

Temperatures are already very high across the Arctic, as illustrated by the image below, showing that on July 16, 2016, it was 1.6°C or 34.8°F over the North Pole (top green circle), while it was 32.7°C or 90.8°F at a location close to where the Mackenzie River flows into the Arctic Ocean (bottom green circle).

Arctic sea ice is in a very bad shape, as also illustrated by the Naval Research Laboratory nowcast below.

Sea ice thickness has fallen dramatically over the years, especially the ice that was more than 2.5 m thick. The image below compares the Arctic sea ice thickness (in m) on July 15, for the years from 2012 (left panel) to 2015 (right panel), using Naval Research Laboratory images.

|

| [ Click on image to enlarge ] |

The image below shows sea surface temperature anomalies from 1961-1990 on July 24, 2016.

Sea surface temperatures off the coast of America are high and much of this ocean heat will be carried by the Gulf Stream toward the Arctic Ocean over the next few months.

On July 24, 2016, sea surface temperature near Florida was as high as 33.2°C or 91.7°F, an anomaly of 3.7°C or 6.6°F from 1981-2011 (bottom green circle), while sea surface temperature near Svalbard was as high as 17.3°C or 63.2°F, an anomaly of 12.6°C or 22.8°F from 1981-2011 (top green circle).

A cold freshwater (i.e. low salinity) lid sits on top of the ocean and this lid is fed by precipitation (rain, hail, snow, etc.), melting sea ice (and icebergs) and water running off the land (from rivers and melting glaciers on land). This lid reduces heat transfer from ocean to atmosphere, and thus contributes to a warmer North Atlantic where huge amounts of heat are now carried underneath this lid toward the Arctic Ocean. The danger is that more ocean heat arriving in the Arctic Ocean will destabilize clathrates at the seafloor and result in huge methane eruptions, as discussed in earlier posts such as

this one.

As temperatures keep rising, snow and ice in the Arctic will decline. This could result in some 1.6°C or 2.88°F of warming due to albedo changes (i.e. due to decline both of Arctic sea ice and of snow and ice cover on land). Additionally, some 1.1°C or 2°F of warming could result from methane releases from clathrates at the seafloor of the world's oceans. As discussed in an

earlier post, this could eventuate as part of a rise from pre-industrial levels of as much as 10°C or 18°F, by the year 2026.

|

| [ click on image to enlarge ] |

The impact of rising temperatures will be felt firstly and most strongly in the Arctic, where global warming is accelerating due to numerous

feedbacks that can act as self-reinforcing cycles.

Already now, this is sparking wildfires across the Arctic.

Above image shows wildfires (indicated by the red dots) in Alaska and north Canada, on July 15, 2016.

The image on the right shows smoke arising from wildfires on Siberia. The image below shows that, on July 18, 2016, levels of carbon monoxide (CO) over Siberia were as high as 32318 ppb, and in an area with carbon dioxide (CO2) levels as low as 345 ppm, CO2 reached levels as high as 650 ppm on that day.

|

| [ click on images to enlarge them ] |

The image below shows the extent of smoke from wildfires in Siberia on July 23, 2016.

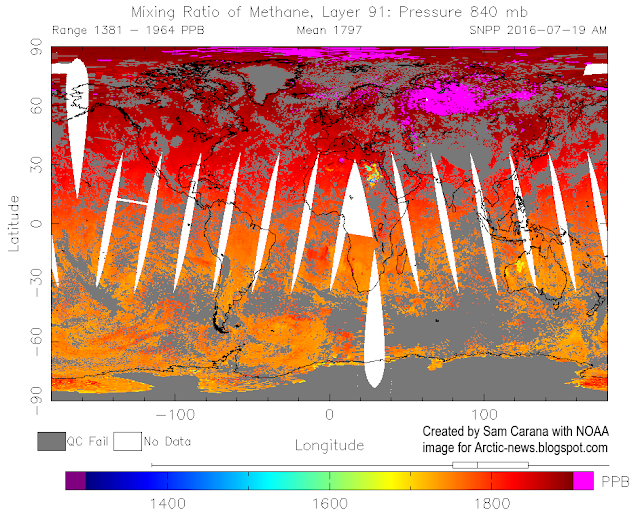

The image below shows high methane levels over Siberia on July 19, 2016.

The image below, from the MetOp satellite, shows high methane levels over Siberia on July 21, 2016.

Below are further images depicting mean global methane levels, from 1980-2016 (left) and 2012-2016 (right).

The image below shows methane levels at Barrow, Alaska.

The image below shows that, while methane levels may appear to have remained stable over the past year when taking measurements at ground level, at higher altitudes they have risen strongly.

The conversion table below shows the altitude equivalents in feet, m and mb.

| 57016 feet | 44690 feet | 36850 feet | 30570 feet | 25544 feet | 19820 feet | 14385 feet | 8368 feet | 1916 feet |

| 17378 m | 13621 m | 11232 m | 9318 m | 7786 m | 6041 m | 4384 m | 2551 m | 584 m |

| 74 mb | 147 mb | 218 mb | 293 mb | 367 mb | 469 mb | 586 mb | 742 mb | 945 mb |

The situation is dire and calls for comprehensive and effective action, as described at the

Climate Plan.