Have a look at the picture below. It shows a graph based on data calculated by the Pan-Arctic Ice Ocean Modeling and Assimilation System (PIOMAS) developed at the

Applied Physics Laboratory/Polar Science Center at the University of Washington.

The PIOMAS data for the annual minimum values are the black dots. The trend (in red) is added by

Wipneus and points at 2015 as the year when ice volume will reach zero. Note that the red line points at the start of the year 2015. The minimum in September 2014 will be already be close to zero, with perhaps a few hundred cubic km remaining just north of Greenland and Canada.

Above image, again based on PIOMAS data, shows trends added by

Wipneus for each month of the year. The black line shows that the average for the month September looks set to reach zero a few months into the year 2015, while the average for October (purple line) will reach zero before the start of the year 2016. Similarly, the average for August (red line) looks set to reach zero before the start of the year 2016.

In conclusion, it looks like there will be no sea ice from August 2015 through to October 2015, while a further three months look set to reach zero in 2017, 2018 and 2019 (respectively July, November and June). Before the start of the year 2020, in other words, there will be zero sea ice for the six months from June through to November.

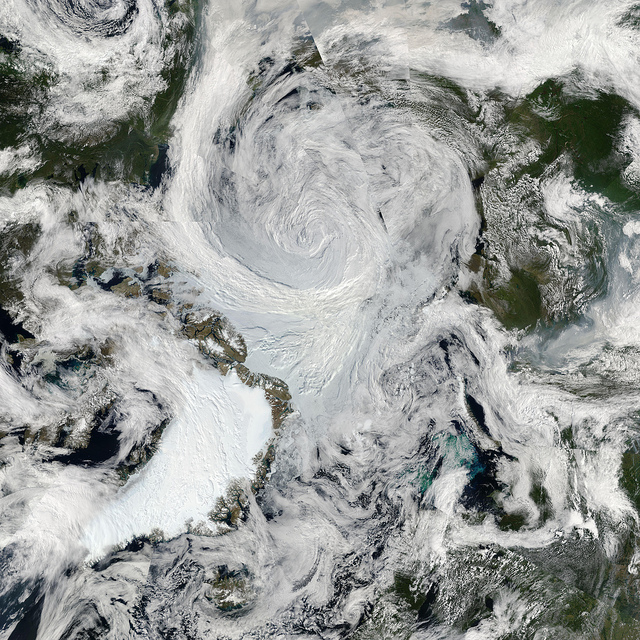

Actually, events may unfold even more rapidly. As the ice gets thinner, it becomes more prone to break up if there are storms. At the same time, the frequency and intensity of storms looks set to increase as temperatures rise and as there will be more open water in the Arctic Ocean.

Above photo features Peter Wadhams, professor of Ocean Physics, and Head of the Polar Ocean Physics Group in the Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics, University of Cambridge. Professor Wadhams has been measuring the sea ice in the Arctic for the 40 years, getting underneath the ice with the assistance of submarines, collecting ice thickness data and monitoring the thinning of the ice. This enabled 1970s data and 1980s data to be compared, which showed that the ice had thinned by about 15%. Satellite measurements only started in 1979.

Thinning of the ice is only one of the problems. "The next stage will be a collapse," Professor Wadhams warns, "where the winter growth is more than offset by the summer melt. If we look at the volume of ice that is present in the summer, the trend is so rapidly downwards that this collapse might happen within three or four years."

Apart from melting, strong winds can also influence sea ice extent, as happened in 2007 when much ice was driven across the Arctic Ocean by southerly winds. The fact that this occurred can only lead us to conclude that this could happen again. Natural variability offers no reason to rule out such a collapse, since natural variability works both ways, it could bring about such a collapse either earlier or later than models indicate.

In fact, the thinner the sea ice gets, the more likely an early collapse is to occur. It is accepted science that global warming will increase the intensity of extreme weather events, so more heavy winds and more intense storms can be expected to increasingly break up the remaining ice, both mechanically and by enhancing ocean heat transfer to the under-ice surface.

,+Sep+9,+2012.jpg)

,+August+27,+2012.png)