“The smart way to keep people passive and obedient is to strictly limit the spectrum of acceptable opinion, but allow very lively debate within that spectrum.” Noam Chomsky (1998).

The level of atmospheric methane, a poisonous gas considered responsible for major mass extinction events in the past, has nearly tripled during the 20-21st centuries, from ~722 ppb (parts per billion) to above ~1866 ppb, currently reinforced by coal seam gas (CSG) emissions. As the concentration of atmospheric methane from thawing Arctic permafrost, from Arctic sediments and from marshlands worldwide is rising, the hydrocarbon industry, subsidized by governments, is progressively enhancing global warming by extracting coal seam gas in defiance of every international agreement.

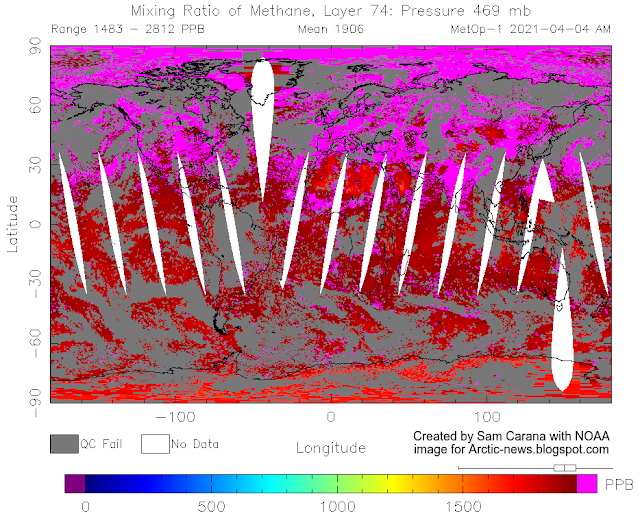

Methane (CH₄), a powerful greenhouse gas ~80 times the radiative power of carbon dioxide (CO₂) when fresh, sourced in from anaerobic decomposition in wetlands, rice fields, emission from animals, fermentation, animal waste, biomass burning, charcoal combustion and anaerobic decomposition of organic waste, is enriched by melting of leaking permafrost, leaks from sediments of the continental shelf (Figure 1) and extraction as coal seam gas (CSG). The addition to the atmosphere of even a part of the estimated 1,400 billion tons of carbon (GtC) from Arctic permafrost would destine the Earth to temperatures higher than 4 degrees Celsius and thereby demise of the biosphere life support systems.

Since the onset of the Industrial age global emissions of carbon have reached near-600 billion tonnes of carbon (>2100 billion tonnes CO₂) at a rate faster than during the demise of dinosaurs. According to research published in Nature Geoscience, CO₂ is being added to the atmosphere at least ten times faster than during a major warming event about 55 million years ago.

Australia, possessing an abundance of natural gas, namely methane resources, is on track to become the world's largest exporter. Leaks from hydraulic fracturing (fracking) production wells, transport and residues of combustion are bound to contribute significantly to atmospheric methane. However, despite economic objections, not to mention accelerating global warming, natural gas from coal seam gas, liquefied to -161°C, is favored by the government for domestic use as well as exported around the world.

In the Hunter Valley, NSW, release of methane from open-cut coal mining reached above 3000 ppb. In the US methane released in some coal seam gas fields constitutes between 2 and 17 per cent of the emissions.

While natural gas typically emits between 50 and 60 percent less CO₂ than coal when burned, the drilling and extraction of natural gas from wells, fugitive emissions, leaks from transportation in pipelines result in enrichment of the atmosphere in methane, the main component of natural gas, 34 times stronger than CO₂ at trapping heat over a 100-year period and 86 times stronger over 20 years. So, while natural gas when burned emits less CO₂ than coal, that doesn’t mean that it’s clean – the reason summed up in one word: methane.

Global warming triggered by the massive release of CO₂ may be catastrophic, but release of CH₄ from methane hydrates may be apocalyptic. According to Brand et al. (2016), the release of methane from permafrost and shelf sediment has constituted the ultimate source and cause for the dramatic life-changing global warming. The mass extinction at the end of the Permian 251 million years ago, when 96 percent of species was lost, holds an important lesson for humanity regarding greenhouse gas emissions, global warming, and the life support system of the planet (Brand et al. 2016, Methane Hydrate: Killer cause of Earth's greatest mass extinction).

The pledge for zero-emissions by 2050 is questioned as governments continue to subsidize, mine and export hydrocarbons. Examples include Saudi-Arabia, the Gulf States, Russia, Norway and Australia. A mostly compliant media highlights a zero-emission pledge, but is reluctant to report the scale of exported emissions as well as the ultimate consequences of the open-ended rise of global temperatures.

Norway, a country committed to domestic clean energy, is conducting large scale drilling for Atlantic and Arctic oil. Australia, the fourth-largest producer of coal, with 6.9% of global production, is the biggest net exporter, with 32% of global exports in 2016. 23 new coal projects are proposed n the Hunter Valley, NSW, with a production capacity equivalent to 15 Adani-sized mines.

Australian electricity generation is dominated by fossil fuel and about 17% renewable energy. Fossil fuel subsidies hit $10.3 billion in 2020-21, about twice the investment in solar energy in 2019-2020. State Governments spent $1.2 billion subsidizing exploration, refurbishing coal ports, railways and power stations and funding “clean coal” research, ignoring the pledge for “zero emissions by 2050”.

The pledge overlooks the global amplifying effects of cumulative greenhouse gases. At the current rate of emissions, atmospheric CO₂ levels would be near 500 ppm CO₂ by 2050, generating warming of the oceans (expelling CO₂), decreased albedo due to melting of ice, release of methane, desiccated vegetation and extensive fires.

Claims of “clean coal”, “clean gas” and “clean hydrogen” ignore the contribution of these methods to the rise in greenhouse gases. Coal seam gas has become an additional source of methane which has an 80 times more powerful greenhouse effect than CO₂. This adds to the methane leaked from Arctic permafrost, with atmospheric methane rising from ~ 600 parts per billion early last century to higher than 2000 ppb. In the Hunter Valley, NSW, release of methane from open-cut coal mining reached above 3000 ppb. In the US, methane released in some coal seam gas fields constitutes between 2 and 17 per cent of the emissions.

The critical index of global warming, rarely mentioned by politicians or the media, is the atmospheric concentration of CO₂. During 2020-2021 CO₂ rose from 416.45 to 419.05 parts per million at a rate of 2.6 ppm/year, a trend unprecedented in the geological record of the last 55 million years. The combined effects of greenhouse gases such as cabon dioxide (CO₂), methane (CH₄) and nitrous oxide (N₂O) have reached near ~500 ppm CO2-equivalent.

Since 1880, the world has warmed by 1.09 degrees Celsius on average, near ~1.5°C on the continents and ~2.2°C in the Arctic, with the five warmest years on record during 2015-2020. Since the 1980s, the wildfire season has lengthened across a quarter of the world's vegetated surface. As extensive parts of Earth are burning, “forever wars” keep looming.

Earth and Paleo-climate scientist

The University of New South Wales,

Kensington NSW 2052 Australia

The Asteroid Impact Connection of Planetary Evolution

http://www.springer.com/gp/book/9789400763272

The Archaean: Geological and Geochemical Windows into the Early Earth

http://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783319079073

Climate, Fire and Human Evolution: The Deep Time Dimensions of the Anthropocene

http://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783319225111

The Plutocene: Blueprints for a Post-Anthropocene Greenhouse Earth

http://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783319572369

Evolution of the Atmosphere, Fire and the Anthropocene Climate Event Horizon

http://www.springer.com/gp/book/9789400773318

From Stars to Brains: Milestones in the Planetary Evolution of Life and Intelligence

https://www.springer.com/us/book/9783030106027

Asteroids Impacts, Crustal Evolution and Related Mineral Systems with Special Reference to Australia

http://www.springer.com/us/book/9783319745442

The Event Horizon: Homo Prometheus and the Climate Catastrophe

https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783030547332